Although Russia’s colonization of the territory remains a relatively obscure chapter in world history, the acquisition of Alaska by the administration of President Andrew Johnson has had enormous economic and strategic value for the U.S. In the history of American land deals, it is second in importance only to the Louisiana Purchase.

For Russia, the sale was the logical conclusion of a colonial venture that had begun with the first Russian landing on Alaska’s shores in 1732. This endeavor, based on a lucrative trade in the luxurious pelts of sea otters, had become shaky by the early decades of the 19th century, when 700 Russians, strung largely along the coast, were trying to exert sovereignty over hundreds of thousands of square miles of territory in the face of increasing British and U.S. encroachment. In the words of Ty Dilliplane, an archaeologist specializing in Alaska’s Russian period, the remote territory was the “Siberia of Siberia”—a place hard to supply and even harder to defend.

Not everyone in the U.S. saw the Alaska purchase as a bonanza. Critics of Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward, who oversaw the negotiations with Russia, derided America’s purchase of this northern territory — twice the size of Texas — as “Seward’s Folly,” “Johnson’s polar bear park” and “Walrussia.” But today—given Alaska’s key military and strategic importance in the Arctic, its huge stores of oil and gas, its enormous quantities of salmon and other fish, and its seemingly limitless expanses of wilderness, which cover most of the state’s 663,000 square miles — it’s hard to imagine the U.S. without its Last Frontier.

Today, a century and a half after the Russians decamped, vestiges of the tsars’ colonial enterprise remain. The most obvious legacy is on a map, where Russian names mark point after point, from the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea to Baranof Island in southeast Alaska to all the streets, cities, islands, capes, and bays in between with names like Kalifornsky, Nikiski Chichagof, Romanzof, and Tsaritsa.

By far the strongest living legacy of the Russian colonial era is the Russian Orthodox Church, most of whose worshippers are Alaska natives or the offspring of Russian-native unions. Intermarriage between Russian colonizers and indigenous people from groups such as the Aleut, Alutiq, and Athabaskan was widespread, and today roughly 26,000 of their descendants—known since the colonial era as Creoles—worship in nearly a hundred Russian Orthodox churches statewide.

“That number may seem insignificant, but consider that about half of Alaska’s population [of 740,000] lives in and around Anchorage and that there are entire regions—the Aleutian Islands, Kodiak Island, Prince William Sound, and the Kuskokwim-Yukon Delta—where the Orthodox church is the only church in town,” says Father Michael Oleksa, a leading historian of Russian Orthodoxy in Alaska. “Small as we are numerically, we cover a huge area.” These legacy communities are supplemented by newer settlements of Old Believers, a Russian Orthodox splinter group that arrived in Alaska in the second half of the 20th century.

Three of Alaska’s Russian Orthodox churches have been designated National Historic Landmarks, and 36 are on the National Register of Historic Places. One of them is the Holy Transfiguration of Our Lord Chapel in Ninilchik, built in 1901. On a blustery March afternoon I stood in the cemetery next to the church, where weathered, listing white Orthodox crosses were interspersed among more modern gravestones bearing names like Oskolkoff, Kvasnikoff, and Demidoff. From the bluff above the village, I looked down on a ramshackle collection of wooden houses and across Cook Inlet to the towering, snowy peaks of the Chigmit Mountains. Gazing past the onion domes, I found it easy to imagine that I was not in the U.S. but in some rugged backwater of the Russian Far East.

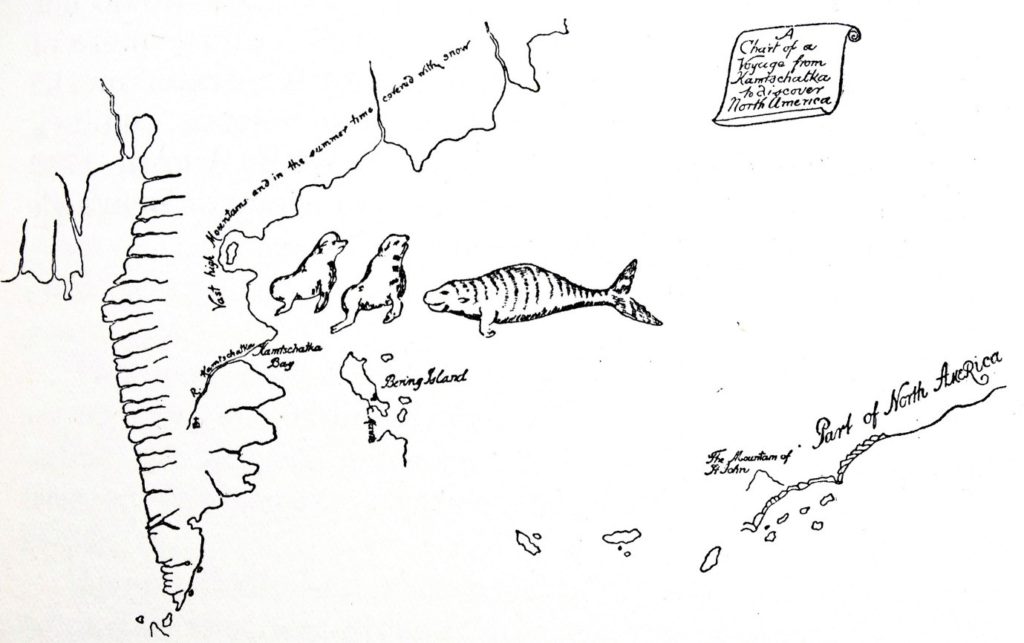

Russia’s expansion into Alaska was an extension of its rapid eastward advance across Siberia in the 16th and 17th centuries. Cossacks, joined by merchants and trappers known as promyshlenniki, hunted ermine, mink, sable, fox, and other furbearers as they subjugated, slaughtered, co-opted, and extracted payments from Siberian indigenous groups. By 1639 the promyshlenniki had reached the Pacific Ocean, and roughly a century later the tsars dispatched navigators such as Vitus Bering to explore the Aleutian Islands and sail deep into Alaska waters. What they found in abundance were sea otters, whose furs would soon become the most sought after in the world, used for everything from the collars of tsarist officers’ coats to jackets for Chinese nobles. The Russian-driven slaughter of the otters would eventually nearly extirpate the original population of 300,000 in the waters of Alaska and the northern Pacific.

By hostage-taking and killing, Russian promyshlenniki subjugated the indigenous Aleuts, who were skilled at hunting sea otters from their kayaks, and pressed them into service as the chief procurers of otter pelts. Government support of the promyshlenniki’s efforts in Alaska gradually increased, culminating in 1799, when Tsar Paul I granted a charter to the Russian-American Company to hunt furbearing animals in Alaska. In effect, the company ran the colony until the territory was sold in 1867.

“Alaska was certainly a colonial venture, but without a strategic plan,” says S. Frederick Starr, a Russia scholar with the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies who has studied Alaska’s Russian period. “The Russians groped their way into it, with the government supporting these venturesome guys who were basically after pelts. The whole story suggests a kind of haphazard, unfocused quality, though there are moments when they try to get their act together and send out bright people to turn it into a real colony.”

Unearthing remains of the Russian colonial period has fallen to the likes of archaeologist Dave McMahan, a soft-spoken 61 year old who served from 2003 to 2013 as Alaska’s state archaeologist. Long fascinated by the colonial period, McMahan became especially intrigued by the fate of a star-crossed Russian vessel, the Neva, which played a pivotal role in the Alaska colony.

A 110-foot frigate, the Neva was one of the first two Russian ships to circumnavigate the globe, an expedition that lasted from 1803 to 1806. During that voyage the Neva stopped in Sitka, where it played a decisive role in a Russian victory over the native Tlingit. It later became one of the vessels supplying the Alaska colony from St. Petersburg.

On January 9, 1813, the Neva was within 25 miles of Sitka when it ran aground in thick fog. It was pounded against the rocks a few hundred yards off Kruzof Island, a 23-mile-long link in the Alexander Archipelago that’s dominated by a dormant, 3,200-foot volcano, Mount Edgecumbe. Thirty-two people drowned in the frigid water; 28 made it ashore, where two soon died. Twenty-four days later a rescue party from Sitka picked up the survivors.

The sinking of the Neva was legendary in Alaska maritime lore, not least because of rumors that the ship was carrying gold. “Like all good shipwrecks in Alaska, the interest was all about the wealth that supposedly was on board,” says McMahan. However, he notes, no Russian-American Company records support the claim that the Neva was laden with precious metals.

Using survivor accounts, satellite and aerial photographs, and the tale of an abalone diver who’d seen cannons in the waters off Kruzof Island, McMahan calculated where the ship likely had gone down and where the survivors might have huddled onshore. “Everything pointed to this one spot,” he says.

In the summer of 2012 McMahan and his colleagues went ashore on a storm-tossed stretch of beach. Above it, on a terrace, their metal detector got a major hit. Digging down, they found a cache of nine Russian axes from the early 19th century, identifiable by a distinctive barb on the blade’s head. “We were just in shock,” recalls McMahan.

Confident that they’d found the survivors’ camp, McMahan and his co-workers sought permission to explore further from the U.S. Forest Service and the Sitka tribe, whose traditional territory encompasses the area, and secured funding from the National Science Foundation. It took three years to clear those hurdles, and last July, McMahan and a team of eight Russians, Canadians, and Americans returned to Kruzof for an arduous dig, plagued by near-constant rain and a handful of grizzly bears that kept wandering past their camp to feast on a rotting whale carcass at the water’s edge. The team uncovered dozens of artifacts that pointed to a group of people struggling to stay alive until they were rescued: a crude fishhook made of copper, gunflints that had been adapted to strike against rock to start a fire, musket balls that had been whittled down to fit guns of a different caliber. They also found part of a navigational instrument, ship spikes, and food middens.

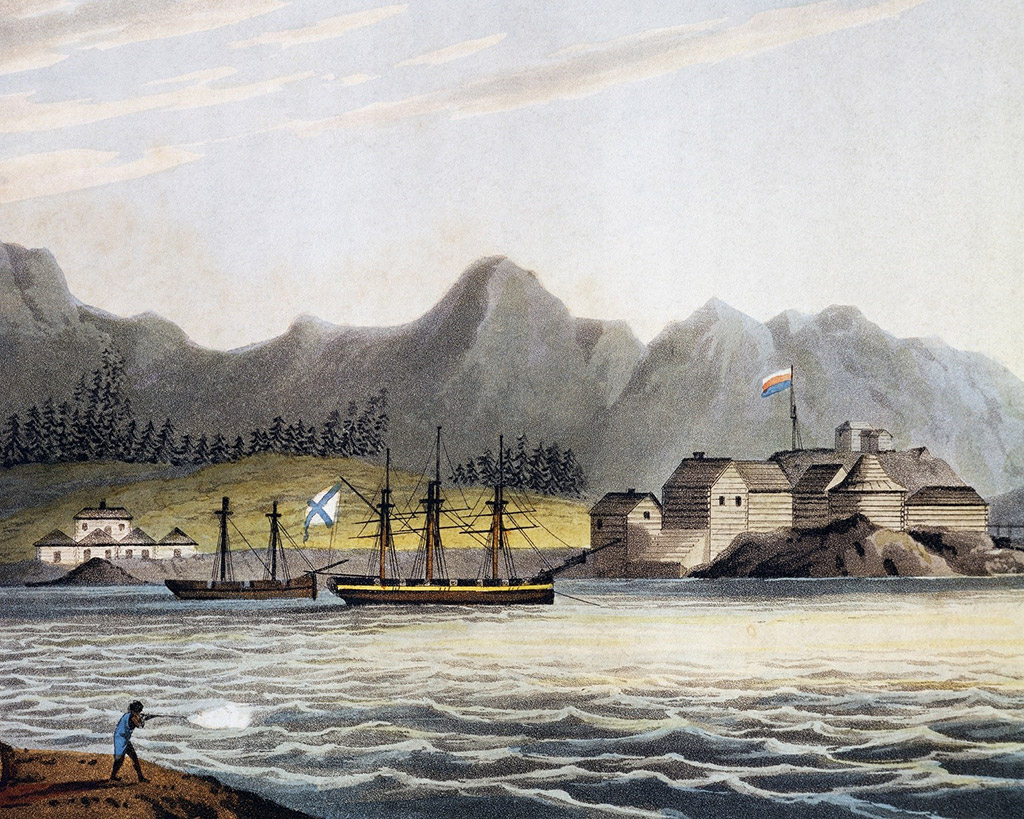

The Neva’s intended destination was Sitka, known then as Novo Arkhangelsk (New Archangel). The outpost served from 1808 to 1867 as the headquarters of the Russian-American Company and for a time was the largest port on the Pacific coast of North America. Rising above the center of the present-day city, population 9,000, is Castle Hill, the site of the company’s buildings, now long gone. McMahan was the lead archaeologist on a dig at the site in the 1990s that turned up roughly 300,000 artifacts, many of them attesting to the cosmopolitan nature of Sitka in the 19th century: Ottoman pipes, Japanese coins, Chinese porcelain, English stoneware, and French gun parts. Sitka then had its own museum, library, and teahouses and became known as the Paris of the Pacific—hyperbole, to be sure, but Sitka was the best this untamed land had to offer.

One of the residents with a direct link to the town’s Russian history is 79-year-old Willis Osbakken. His grandmother—Anna Schmakoff, whom he knew as a boy—was of Russian-Alaska native descent. She was born in 1860 and before she died, in 1942, was one of the last people alive to have witnessed the historic 1867 transfer ceremony on Castle Hill, when the Russian flag was lowered and the U.S. flag raised. Schmakoff, then seven years old, recalled one thing above all, Osbakken says. “She didn’t really understand why all the Russian people were crying. But her impression was that they were crying because the American flag was so much prettier than the Russian one.”

In the heart of Sitka sits the handsome, gray wooden St. Michael’s Cathedral, built in the 1840s and long the seat of the Russian Orthodox bishop of Alaska. The cathedral burned down in 1966, and later was rebuilt and restored to its original condition, with sailcloth covering the walls and silver, brass, and gold icons glittering under a graceful dome. Attendance at St. Michael’s has dwindled to a few dozen regular worshippers. But Father Oleksa says that although Alaska’s Russian Orthodox Church is losing members in larger towns and cities, it’s still going strong in rural areas and native villages.

“Secular trends are not as powerful,” he says. “The simple reason is that whether it’s agrarian living or subsistence hunting and fishing, the more your life depends on a direct relationship with the natural world, the more religious people tend to be.”

The church’s continuing strength among Alaska natives is largely because the church defended indigenous rights during the Russian period, frequently clashing with the Russian-American Company over its mistreatment of the native population. Church leaders, particularly Ivan Veniaminov, later canonized as St. Innocent of Alaska, supported native culture and held church services in indigenous tongues—all in contrast to many future Protestant and Catholic missionaries.

In the last decades of Russian rule the Russian-American Company supported the church and its schools and began to treat the indigenous people more humanely. But by the 1850s Russia’s Alaska adventure was becoming increasingly untenable. Sea otter populations had been nearly depleted. In 1856 Britain, France, and Turkey defeated the Russians in Crimea, and Tsar Alexander II was preoccupied with paying for the war, enacting military and legal reforms, and freeing Russia’s serfs. The California gold rush, which began in 1848, also drove home to the tsar that if gold ever were discovered in Alaska, there was no way the feeble Russian presence could hold back a flood of Americans and Canadians.

“This was just one step too far for them, and so they said, To hell with it—we’ll sell,” says Starr. “It was an offer of real money at a time when they really needed it.” And by selling to the U.S., a close ally, Russia would forever keep Alaska out of the hands of Great Britain’s Canadian dominion.

When Russia transferred Alaska to the United States, the tsar handed over sovereignty of the territory, but the property rights of Alaska natives were ignored. For the next century the indigenous peoples and the U.S. government battled over the issue. It was finally resolved in 1971, when the U.S. Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, under which the government paid nearly a billion dollars to Alaska’s indigenous peoples and returned 40 million acres to native groups.

In effect, the American government bought Alaska a second time. And on this occasion Washington had to dig far deeper into its pockets than it had 104 years before.

For the complete story, click here.

Source: SMITHSONIAN Journeys QUARTERLY

July 7, 2016